The second-longest strike in Writers Guild of America history came to an end on September 26, and while a deal with actors still needs to be hammered out, it’s impossible to overstate the joy and relief so many in the industry are feeling right now. Even if the new deal doesn’t solve the many problems facing the entertainment industry at the macro level, the WGA won big in its battle with the studios, securing gains that will make a real difference in its members’ lives. And yet it’s not just euphoric vibes floating around Hollywood; there’s also a sense of disbelief — and even anger — that it took 148 days of collective misery to arrive at an agreement whose specifics were hammered out in less than a week of actual bargaining. As one veteran writer puts it, “These companies destroyed people’s lives for five months for no fucking reason when they could have made this same deal on day one.”

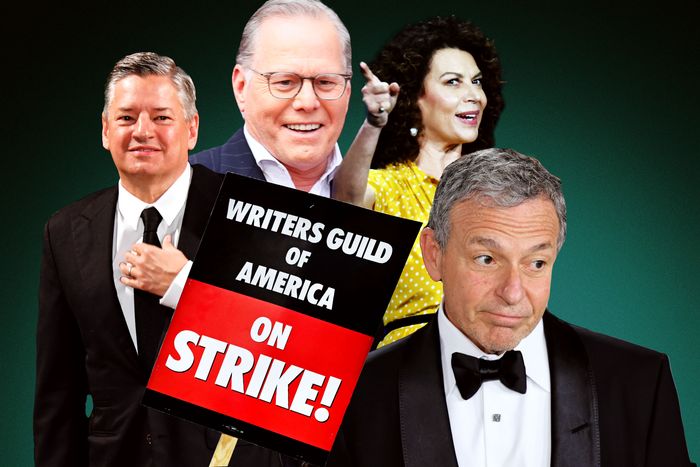

Even those who argue that the guild is not blameless concede that the summer of suffering was entirely unnecessary. “Given where they ended up, it never needed to go this long,” one executive-suite veteran concludes. Another source on the studio side goes even further, arguing that even if you share the management opinion that the WGA has become “radicalized” in recent years, it’s hard not to conclude that the failings of the CEOs who drove the negotiating strategy of the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers made things worse. “David Zaslav has never dealt with labor at this level, Bob Iger is clearly preoccupied with cleaning up his mess, Donna Langley doesn’t really know television, and Ted Sarandos was the architect of a lot of the problems the industry has,” the source says. “And then you had Carol Lombardini at the AMPTP, who was fighting the last war [over previous contracts]. It was bad all around.”

When TV historians start trying to make sense of this summer, one of the biggest subjects of debate will likely revolve around why Hollywood conglomerates opted to bring their businesses to a screeching halt at the same time they were already deep in crisis with the grim new post-peak-TV reality. The executive-incompetence theory is certainly one possibility, but to others, the motivating factor was even more basic: money. “They really didn’t have any interest in resolving things before putting a couple quarters’ worth of savings into their pockets,” the veteran exec says, echoing a sentiment heard often from industry insiders even before the strikes began. Burdened by streaming debt and the market’s pivot toward valuing profitability over subscriber growth, the entertainment giants figured that freezing spending for a few months would be good for their short-term bottom line. At the same time, the studios hoped that a weakened WGA would settle for a less costly deal, saving a few more nickels — and, more importantly, making the gods of Wall Street happy. They also figured that they’d quickly make deals with both the Directors Guild of America and Screen Actors Guild, putting even more pressure on writers to settle for less.

Of course, that’s not what happened. While the DGA settled for the relative crumbs offered by the AMPTP, the Fran Drescher–led SAG didn’t bite and ended up striking in mid-July. The actor walkout left many studio sources I spoke to genuinely shocked. SAG’s move also gave writers a huge boost in energy and leverage, turning what many at the studios expected to be a two- or three-month pause into a five-month disaster. “When SAG went out, anybody with half a brain knew this was different,” one longtime showrunner says. In theory, this labor solidarity ought to have prompted the studios to start making serious concessions and sent the CEOs to the bargaining table immediately. Instead, two more months passed during which there was very little movement — but a lot more pain, particularly for workers. “The absolute hard-assery of the media conglomerates during these negotiations was completely immoral,” the veteran writer says, a judgment echoed by the longtime showrunner: “This whole thing didn’t have to hurt as many people as it did for so long,” he says. “That’s a choice the studios made, and it’s a devastating moral indictment.”

But it would be wrong to suggest the studios simply lost the war that played out over the last five months. Fact is, at almost every turn, the Hollywood unions won in their battles with management, with victories big (WGA-SAG solidarity, showrunners sticking by their less-compensated staff writers, public opinion) and small (shutting down filming of TV shows and movies before the SAG walkout, getting Drew Barrymore and Bill Maher to reverse return-to-work plans). “The studios got outplayed by the Writers Guild,” says Cynthia Littleton, co-editor-in-chief of industry bible Variety and the author of TV on Strike: Why Hollywood Went to War Over the Internet, which chronicled the saga of the 2007–08 WGA work stoppage. Littleton argues that the WGA “had goals and a pretty clear strategy on how to get there,” along with what she labels the guild’s secret weapon: its rank-and-file members. “The studios, with all their money, had nothing like the force of the WGA membership,” she says. By contrast, “The AMPTP had a policy agenda, which is different from a strategy. It was playing a very traditional ground war, and it absolutely didn’t work in this environment.”

Indeed, Littleton and sources on both the writers’ and studios’ sides cite member action — particularly on social media — as playing a significant role in the outcome of the strike. During the early days of the walkout, Twitter helped the WGA mobilize members to target movies and shows still in production, shutting them down well before the SAG strike started. “Twitter suddenly became very useful again,” one writer quips. “Someone like Warren Leight in New York would start tweeting about where they needed members and I could amplify it from all the way in Los Angeles. We were able to have each other’s backs in a way that was unprecedented.”

What’s more, social media served as a daily antidote against flagging morale and a tool to fight back against attempts by the studios to spin the narrative of the strike via media leaks. When stories about showrunners pushing WGA leadership on the status of strike talks started to surface, writers flooded Twitter to tamp down suggestions that these conversations were signs of weakening solidarity. “The moment anything like that came out, we had a way of communicating our side,” the WGA writer says. The power of social media to shame dissenters also likely convinced any wavering showrunners to keep disagreements largely to themselves. “Some showrunners got away with undercutting their own guild in 2008 in a way that would not be allowed today,” the veteran showrunner says. “I mean, they beat the crap out of Drew Barrymore.”

Collectively, all of these factors resulted in what was accomplished this week: a new deal between the WGA and studios far better than most industry insiders predicted before the guild walked out in May. To be sure, the victory the guild scored does not mean it got every specific ask it made before walking out. But the AMPTP was forced to make significant concessions in every major area of concern laid out by the WGA, even after the studios had insisted for months that such issues — like minimum staffing size or performance-based bonuses — were nonstarters. The WGA also notched wins with smaller items over which it had been unsuccessful for decades. “There’s no way to spin this: It’s a huge win for the WGA,” Littleton says.

Among the highlights:

➼ Streaming residuals will be tied to a show’s performance. For the first time in a guild contract, streamers have agreed to performance-based residuals, something they once vowed would never happen. Starting next year, if an original show or movie produced for a streaming platform is viewed by the equivalent of 20 percent of said platforms’s domestic subscriber base within 90 days of premiere, writers will get a bonus on top of existing residuals (as much as $16,400 for TV episodes and $40,500 for movies with a budget of at least $30 million). That bonus rate will continue in the future if a show once again reaches the 20 percent threshold during a 90-day window in a new calendar year. It’s a significant concession by the studios, who had long argued that they were already rewarding creators by paying them much more money upfront than networks in the linear age. And yet this breakthrough concession also comes with some major asterisks.

For one thing, the new terms won’t apply to older library shows (sorry, BoJack Horseman) or a library series produced for linear. Those Suits and Ballers reruns that have been killing it on Netflix this summer? No extra coin for them. Plus, industry insiders say only a small percentage of streaming originals will likely manage to break the 20 percent barrier, based on the limited viewership data we’ve seen to date. “It’s going to be a high bar to clear,” Littleton says. But the real win for the WGA here was simply getting studios to let the guild see their data and agree to the concept that big hits should be valued at a different level. “No, Suits or the next NBC drama that gets remaindered and sent to Netflix won’t see anything, but our foot is in the door,” one showrunner argues. Littleton agrees: “Getting new language into the deal is huge,” she says, and notes that what happened this summer will set the stage for the WGA and other guilds to ask for even more in future negotiations. Littleton adds that a similar situation occurred in 1985 when the WGA got residuals for cable shows and again in 2008 when it got studios to concede that streaming shows have value, period.

➼ Almost all shows will now require a minimum number of writers and guarantees on employment length. This was a big priority for writers, who have seen streamers try to force showrunners into making shows with far fewer writers than historical norms — in part because episode counts have been reduced, but also because production schedules have changed. Now the typical eight- or ten-episode series will be required to employ five writers and at least two of them need to stay on staff for a minimum of 20 weeks. This addresses concerns that the streaming model (including so-called “mini-rooms”) makes it impossible to train the next generation of showrunners, since all episodes of a show are often written before a series begins filming. “Staffing and mini-rooms is a gigantic win,” one showrunner says, arguing that even if the WGA only got about half the number of minimum writers it asked for, the new deal will go a long way toward ensuring younger writers have opportunities to learn the business.

➼ The studios gave writers protection against artificial intelligence. The new deal makes it clear that AI can’t be used to write or rewrite a script, and while studios can use scripts they already own to train AI models, the contract gives the WGA avenues to challenge that use. There are also new rules requiring disclosure when AI tech is used, as well as flexibility for writers who want to use AI as a tool. Once again, nobody thinks this language erases the existential threat AI could pose to creative industries, but Littleton argues that the tech is so new, it might’ve been impossible to come up with language fully acceptable to all. “Nobody can define it, and nobody wants to be trapped into terms that can’t be taken out of a future contract,” she says. “But they had to address it because it had become such an issue with membership.” As with residuals, Littleton thinks the inclusion of AI language — which appears to be the first time any major labor group has won any sort of protection from the emerging technology — serves as a marker for future contract talks. “It’s a big, flashing red light that says they’ll address it in the next talks.”

➼ The WGA secured big wins on “little” issues that have long plagued writers. The studios made many concessions long sought by WGA negotiators on issues that didn’t attract much press during contract talks but are nonetheless incredibly important for many writers. For example, film writers will finally get guaranteed compensation — and get paid more quickly — when they turn in a second draft of a movie. Writing teams working on TV shows will now find it much easier to qualify for WGA health insurance because the full amount of their script fees will count toward annual minimums rather than the portion they split with a partner. And entry-level staff writers will now get paid when they write a script, which, amazingly, didn’t happen before. “They picked so many little things off of their wish list,” Littleton says of the WGA’s negotiating committee. One veteran showrunner agreed, saying he was blown away when he read the details of the new contract on Tuesday. “It’s like you’ve been living in this shitty apartment with leaks and cracks, and then one day, they come in and fix 90 percent of the bad things,” the writer says. “These were marginal items but they got a lot of them. There are dozens of things which will matter to a lot of people.”

While writers are savoring their wins this week and the studios are just glad a deal got done at all, nobody is under the illusion that this agreement is about to solve the real, serious, and even existential threats facing creative talent and their well-compensated bosses. For one thing, a deal with SAG needs to happen before cameras can start rolling on feature films and scripted TV shows. Talks are scheduled to begin on Monday, and there’s optimism the WGA deal will provide a framework for a relatively quick deal. “The conventional wisdom is they’ll close that deal right up,” one studio-side source says, but not without adding a note of caution: “You really can’t count on anything these days.”

Assuming the AMPTP and SAG make peace within a couple weeks and cameras start rolling by the end of October, the TV industry in particular will still be right back where things were before the writers put their digital pencils down in May. “Peak TV was a bubble and that bubble burst,” says one Hollywood exec. Indeed, long before Hot Labor Summer was a reality, streamers were already cutting development staff, reducing series orders, and generally preparing to put the era of 600 scripted shows per year in the rearview mirror.

This is a key fact to keep in mind over the next few months, particularly once a SAG deal is done. The AMPTP and its members have largely stayed quiet this week, offering minimal spin to the Hollywood trades and generally accepting the narrative that they suffered a bruising defeat. But once all the peace treaties — a.k.a. labor deals — are officially ratified and signed, it wouldn’t be surprising to see the studios make use of their considerable PR resources and mount a counteroffensive. We’re already seeing that pop up in places like the New York Times’ podcast The Daily, which tried to pin rising costs for streaming and the coming cutback in TV show orders on the strike. There’s a good chance execs will try to push that narrative in the future, blaming the deep cuts that everyone knows are coming on the gains writers (and presumably actors) got at the bargaining table. Simply put, that’s bull. “People were already pulling back and getting ready to spend less, then there just happened to be a strike,” the veteran exec says. “Maybe the strike sped things along a little bit, but there was already a contraction happening. When bubbles burst, it’s painful.”

Even if studios and streamers opt not to go all in on a “blame labor” strategy to spin the downsizing still to come in the post–Peak TV world, the reality is that there is some serious fence-mending that needs to be done in Hollywood. Yes, writers are overjoyed that the headlines coming out of this week are that labor won in a big battle. They’re also energized to be part of a growing movement of workers standing up against the rising wage gap between labor and management, a divide which is just as real in entertainment, even if, yes, some key pieces of talent are paid huge sums of money. But the aforementioned anger over what just happened is very real. “I will never understand why they had to take that gamble that we’d break,” one simmering writer says. “Just to save what, not even that much money? Why not be human beings? It was shameful behavior. We will conveniently forget about it because we need to work with them. But we will never forgive.”

More About the WGA Strike

- All the Shows Returning After the Writers’ Strike

- SAG Is ‘Ready’ to Take on Studios Next

- The Strike Force Five Return to Their Day Jobs