This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

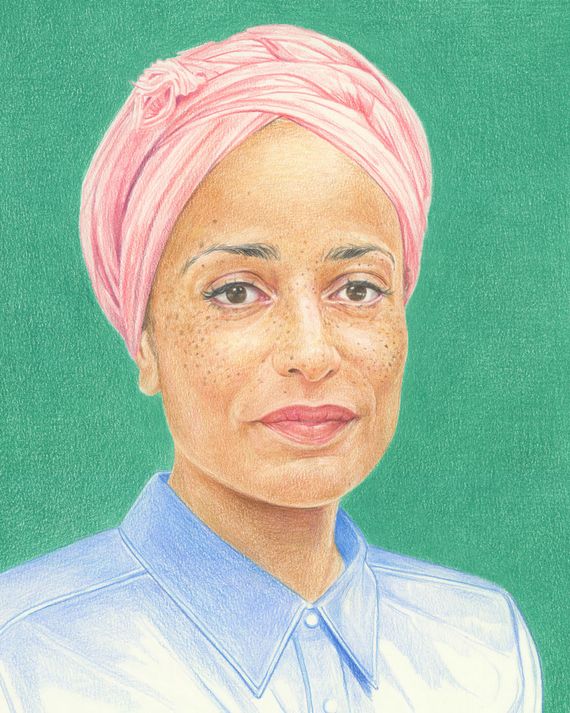

Zadie Smith’s first book, White Teeth, was the English comic novel on bath salts. Published to universal acclaim in 2000, it loosely centered on the Iqbals and the Joneses, two zany families living in Willesden Green, the diverse North London neighborhood where Smith grew up. Her madcap creations lost their teeth, fucked twins, gave birth during earthquakes, predicted the end of the world; there were Irish pubs owned by Iraqis, genetically modified mice, and an Islamic fundamentalist group named KEVIN. (“‘We are aware,’ said Hifan solemnly, pointing to the spot underneath the cupped flame where the initials were minutely embroidered, ‘that we have an acronym problem.’”) All the while, one never lost sight of Smith herself, bursting with exuberance and sincerity. Critics celebrated her for breaking “the iron rule that first fictions should be thin slices of autobiography, served dripping with self-pity,” even as the author’s biographical details — her age (24), her race (Jamaican mother, white father), her looks (good) — would make her an object of fascination. “Is Britishness cream tea and the queen?” asked the New York Times. “Or curry and Zadie Smith?”

But Smith also had her critics. In an infamous review, James Wood dubbed White Teeth a work of “hysterical realism,” arguing that Smith’s characters, though they did possess a certain “shiny externality” reminiscent of Dickens, were “not really alive.” For Wood, a passionate defender of the realist novel, this meant that White Teeth lacked “moral seriousness.” In response, Smith conceded that hysterical realism was “a painfully accurate term for the sort of overblown, manic prose to be found in novels like my own.” As early as 2002, she began to speak of “the morality of the novel,” relocating herself within a tradition that included George Eliot, Henry James, and E. M. Forster. For Smith, this tradition was united in the belief that by enlarging the sphere of plausible others — what Forster once called “likely people” — the novel could act to widen the reader’s moral sympathies. “When we read with fine attention, we find ourselves caring about people who are various, muddled, uncertain, and not quite like us (and this is good),” Smith wrote in a 2003 lecture on Forster, whose Howards End would inspire her genteel third novel, On Beauty. That same year, she tried to read White Teeth for the first time since publication: “I got about ten sentences in before I was overwhelmed with nausea.”

It’s a shame. A novelist has a sacred right to hate her first novel, but White Teeth remains by far the best thing Smith has ever written; what bad luck to have done it by 24! Smith has apparently concluded that White Teeth’s greatest strength, its audacious unreality, was in fact its fatal flaw. Today, she is firmly within the realist camp despite her recurring feints at departure. Her much-debated 2008 essay “Two Paths for the Novel,” which pitted the “lyrical realism” of Balzac and Flaubert against the 20th-century avant-garde, reads now like two paths for Zadie Smith. Every time she has set out down the second path, it has looped consolingly back into the first. On Beauty was a novel of ideas; NW, Smith’s fourth novel, dabbled in Joycean modernism. But each new form has represented a fresh attempt to write the morally serious novel that White Teeth had failed to be. This is Smith: radical for the sake of tradition. In another 2008 essay, this one on Middlemarch, Smith argued that a heightened moral sensitivity drove Eliot to “push the novel’s form to its limits.” But for this very reason, the “George Eliot of today” would need to invent her own forms; she certainly wouldn’t be writing a “nineteenth-century English novel.”

Now Smith has done just that. The Fraud, her first historical novel, depicts the celebrated Tichborne trial of the 1870s through the eyes of Eliza Touchet, real-life cousin by marriage to the minor novelist William Harrison Ainsworth, an erstwhile rival of Dickens. Eliza, a sensitive soul who longs to discover “what could be known of other people,” soon becomes obsessed with key witness Andrew Bogle, an enigmatic, formerly enslaved Jamaican; her fascination will ultimately inspire a novel of her own. The Fraud is thus that irresistible creature: a novel about novels. Like Middlemarch, it is divided into eight volumes, and Eliza even spies Eliot (who privately went by Mrs. Lewes) among the trial’s attendees. “Was this what the admirable Mrs Lewes felt as she worked?” wonders our budding lady novelist as she prepares to write. More than ever, Smith is asking herself the same question. Her two paths for the novel have become a perfect circle: What could be more avant-garde in an age of data harvesting and identity politics than a heartfelt 19th-century novel? The socially minded Eliot believed that through sympathetic portraits of ordinary people, the novel could provide readers with “the raw material of moral sentiment.” With The Fraud, Smith delivers her most passionate defense of this idea to date. Whether it persuades is another matter.

Years of living with a novelist have made Mrs. Touchet suspicious of the whole breed. Smith imagines Eliza as a thwarted intellectual — every Zadie Smith book must have at least one — but the subtle, liberal-minded housekeeper still loves her cousin enough to withhold her dismal view of his turgid historical novels. Eliza has an even poorer opinion of his friend Charles, in whose dark charms she glimpses the “vampiric” attitude of all novelists toward real life. Smith apparently relished writing Dickens’s death into The Fraud; the novel is almost too easily read as a final attempt to wash off the ancient stain of hysterical realism. Wood wrote that Smith had substituted “information” for character, and so here we find a drunk William Thackeray telling Eliza that her cousin “too frequently mistakes information for interest.” Wood accused Smith of Dickensian caricature; Eliza bitterly charges Dickens with turning the people he meets into “cartoons barely worthy of Cruikshank’s inkpot.” One wonders if the sting of these criticisms really has lingered for 20 years; at least we can assume that Eliza too would have hated White Teeth. “God preserve me from novel-writing,” she thinks. “God preserve me from that tragic indulgence, that useless vanity, that blindness!”

But one never seriously supposes Smith has lost her faith in the novel. Eliza must have a change of heart. It comes in the form of the Tichborne case, in which the courts weighed an Australian butcher’s dubious claim to be Sir Roger Tichborne, the long-lost heir to a baronetcy. From the beginning, Eliza regards “Sir Roger” as an obvious fraud, “a man with no centre, who might be nudged in any direction.” But Bogle, formerly a valet to Sir Roger’s uncle, is something different. Eliza sees “nothing hidden or masked” in his face, but this makes him totally “impenetrable,” a cipher without evident motives. Inexplicably, Bogle testifies that the Claimant is the genuine Sir Roger, even as his testimony costs him his pension from the Tichbornes. This sets off a moral crisis in Eliza, whose wonted perspicacity has finally met its match: a man who must be speaking falsely and is nonetheless radiant with truth. As she walks the streets of London taking in the foreign faces — Chinese sailors, an African doctor, a delegation of men in fezzes — Eliza ponders the question raised by Bogle’s very existence: “What can we know of other people?”

Desperately curious, Eliza poses as a journalist and convinces Bogle to tell her “everything.” But his history — his life as an enslaved man in Jamaica, then a man-servant in England — provides few clues to his motives in supporting Sir Roger; on the contrary, it reveals only a cautious, clever man who has won his freedom through “obscure and underhand” means. Upon learning this, Eliza senses that the door to ultimate reality has suddenly come loose: “Finally, she could open it! But to her astonishment, it opened inwards. She had been standing inside the very thing she’d been looking for.” The secret is that there is no secret: Andrew Bogle is simply a person, and as Eliza inwardly exclaims, “A person is a bottomless thing!” One need not believe Bogle to find him believable, the way a character in a good novel is believable. He is one of Forster’s likely people, fully, unfathomably alive. For Eliza, this had always been the failure of her cousin’s drab historical novels; never had there been room for “stories like her own — or for that matter like Mr. Bogle’s. Stories of human beings, struggling, suffering, deluding others and themselves.”

In fact, there is one novel Eliza likes very much. “Just a lot of people going about their lives in a village,” her cousin scoffs when he spots her reading the second volume of Middlemarch. “Is this all that these modern ladies’ novels are to be about? People?” The heart leaps up: Precisely! In that second volume, we find what Smith once called “the most famous lines” in all of Middlemarch: “If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel’s heart beat, and we should die of that roar which lies on the other side of silence.” As Eliza opens herself to Bogle, this roar will begin to split her ears. Just who does she think she is? Certainly Eliza Touchet, whose late husband’s family made their fortune in the transatlantic slave trade, is not the “right” vessel for an enslaved man’s careful ascent to freedom. Bogle’s firebrand son distrusts Eliza’s reformist attitudes, and the life story of Andrew Bogle, presented here in two stand-alone volumes, often resembles the Caribbean slave narratives dictated to well-meaning English abolitionists in the early-19th century. It is quite possible that Eliza’s novel, like the silly ladies’ novels Eliot abhorred, will be “less the result of labor than of busy idleness.”

So perhaps The Fraud expresses an anxiety about the novel equal to its defense of it. “We mistake each other,” Eliza admits, reflecting on how “everything conspires” against the enduring cognizance of other people. But for Smith, the inevitable fraudulence of the novel is precisely what gives it its moral urgency. In a provocative 2019 essay about cultural appropriation, Smith opposed the “popular” idea that “we can and should write only about people who are fundamentally ‘like’ us: racially, sexually, genetically, nationally, politically, personally.” The novelist does presume to know the lives of others, she wrote, but only in order to light up our hidden commonalities as human beings; without this presumption, “we could have no social lives at all.” Thus Eliza’s blind spots, far from disqualifying her, testify to the slow, uncertain work of becoming morally serious. Like Dorothea in Middlemarch, she is reaching imperfectly toward “the fullest truth, the least partial good.” Who does Eliza think she is? Well, a person.

Now Smith would be the first to claim that her defense of the novel, that “indefensible art,” is inherently contradictory. “Ideological inconsistency is, for me, practically an article of faith,” she wrote in the introduction to her first essay collection, Changing My Mind. Smith has often made a virtue of negative capability, Keats’s phrase for how Shakespeare wrote so empathetically that he appeared to hold, in Smith’s words, “no firm opinions or set beliefs.” In a talk given after the 2008 election, Smith ascribed negative capability to Barack Obama, whose biracial heritage had blessed him, as it had her, with the ability to “see a thing from both sides.” There was tremendous credulity here; as the critic Namara Smith has noted, the argument lacked any awareness that the two sides in question “might not be competing on level terrain.” Doubtless, many would no longer stand by what they said in the afterglow of 2008. But the optimism here, far from an Obama-era relic, is just an early instance of a very consistent feature of Smith’s career as a public intellectual: her almost involuntary tendency to reframe all political questions as “human” ones.

This humanist impulse has made for some perennial wrongheadedness. Smith rather famously compared the opponents of a white artist’s controversial painting of Emmett Till to “Nazis,” arguing that all art deserved to be “thought through” on its own terms. The truth is that Smith herself struggles to think in groups of two or more; her habit of sympathizing with the least sympathetic party in any given situation frequently drives her to the political center. In fairness, the Trump years have made her more receptive to Black radicalism, but Smith will still always favor a psychological interpretation over an ideological one. Thus we are asked, in the wake of Brexit, to spare a thought for the white working-class voter who lacked “the perceived moral elevation of acknowledged trauma”; thus we are asked not to call the Charleston church shooting a hate crime since, “when it comes to murder, what other kind of crime is there?” At the same time, Smith regularly confesses that she has “no qualifications to write as I do,” downplaying her own essays as “the useless thoughts of a novelist.” This is disingenuous. She is Zadie Smith. But she appears to have decided at some point that being faintly ridiculous all of the time is preferable to being wrong some of the time.

No surprise that Smith’s most ardent wish these days is for fiction to be a space of freedom from the long teeth of identity. She traces her own desire “to know what it was like to be everybody” back to that “big, colorful, working-class sea” that was Willesden Green. But, for her, negative capability gently dissolves the specific contents of whatever consciousness birthed it. One need not be biracial to write a great novel because all great novelists might as well be biracial, so vast are their powers of empathy. Thus Smith is just as happy to attribute the “empathic imaginative leap” of fiction to David Foster Wallace, a white guy from Illinois who once speculated that “straight white males” may be more alienated than anybody. Smith has similarly warned us off the absolutist belief, vaguely burbling up among her writing students, that a novel’s characters should be judged for how “correctly” they represent the distinctive behaviors of an identity group — that a gay character, for instance, should do things only a “real” gay person would do. “How can such things possibly be claimed absolutely,” Smith asks, “unless we already have some form of fixed caricature in our minds?”

This is a good point. But one should never trust an argument that depends on the anonymous defenestration of undergraduates. Smith’s 2018 short story “Now More Than Ever,” in which professors point enormous arrows at one another to decide who should be canceled next, is proof enough that nothing breeds reaction in the liberal mind like appointment to an American university. “Speaking for myself, I’m the one severely triggered by statements like ‘Chaucer is misogynistic’ or ‘Virginia Woolf was a racist,’” Smith wrote in a self-effacing review of the film Tár. “Not because I can’t see that both statements are partially true, but because I am of that generation whose only real shibboleth was: ‘Is it interesting?’” This is a willful misunderstanding. Of course Woolf’s racism is interesting to those whom Smith calls, with not enough irony, “the youngs.” The problem appears to be that it isn’t interesting to her. But when young people rate a novel poorly because they disagree with its politics, it is more convenient to assert that they have simply abandoned the old-fashioned field of aesthetic inquiry altogether than to reckon with the possibility that aesthetic inquiry itself is being remade. And so Smith congratulates the new generation on preferring politics to aesthetics; the best way to get someone off your lawn is to direct them to a lawn of their own.

This is literary NIMBYism: Yes, politics, but over there. Smith grants that language has become a “convenient battleground” for political aggression given the meager success of intractable (but so admirable!) material struggles around, say, wealth inequality or prison abolition. Still, she insists that fiction cannot afford the “ideology of separatism” that naturally springs up among historically oppressed groups; its business is “with the people, all the people, all the time.” But this too is a political position. As Forster once said of himself, Smith would rather be “a humanist with all his faults, than a fanatic with all his virtues.” She admires the veil of ignorance, a thought experiment devised by the liberal philosopher John Rawls in which a group of rational individuals must organize a society without knowing their place within it. For Smith, the novel is just such an experiment in thinking beyond our closely held identities. It’s true that many bad novels have substituted ideology for interest. It’s equally true that Smith envisions the novel as a little liberal machine for making more little liberals. “We hope all of humanity will reject the project of dehumanization,” she wrote in an essay on Toni Morrison last year. “We hope for a literature — and a society! — that recognizes the somebody in everybody.” Fine words! But they are all gums, and no white teeth.

Suppose Zadie Smith is right. How does fiction arouse our sympathies? One good way is to present people who are “finely aware and richly responsible,” as Henry James wrote, explaining that readers care “comparatively little for what happens to the stupid, the coarse and the blind.” This makes sense: We are moved by Hamlet’s feeling for poor Yorick, not by Yorick himself. But the Jamesian sensitive soul is by now a cliché; it is why so many debut novels maroon us in the minds of characters who sound suspiciously like novelists. Perhaps we will have better luck with one of the blind. Consider Mr. Casaubon, the irritable pedant of Middlemarch. Urging us to make “room” for Casaubon, Eliot tells us that his soul has always been too weighed down by self-doubt to experience true passion: “It went on fluttering in the swampy ground where it was hatched, thinking of its wings and never flying.” Over a century of readers has been moved by this image. But we know that this leaden theologian could never devise a metaphor so delicate — this is Eliot speaking, making him into a likely person. In this respect, Eliot is no different from Hamlet: The more sympathetically she paints her characters, the more we are stirred by her own powers of sympathy.

So how is the author to get out of the way? A traditional solution is free indirect style, a technique as old as Austen, in which the narrator speaks in the voice of a character. Here is Elizabeth Bennett, reading that fateful letter from Mr. Darcy:

How differently did everything now appear in which he was concerned!

Now, here is the same sentence, rewritten as quoted speech:

“How differently everything now appears in which he is concerned!” Elizabeth thought.

Not as compelling! Rather than look down from above, Austen briefly sacrifices her authorial omniscience in order to get in character, narrating Lizzy’s shock as if from within. This technique is now exceedingly common; one finds it all over contemporary fiction, and Smith is quite good at it. “Did he think her a vampire?” she writes in The Fraud, adopting Eliza’s anxiety about Bogle as her own. “She only wanted to know what could be known of other people!”

But Eliza is right to be anxious: One can never quite tell if free indirect style is a gallant deferral to a character or a jostling encroachment on him. Here is Bogle in his part of The Fraud, passing contemplatively by an English forest:

Bogle admired a gold and russet forest as it went by, swaying in the gathering wind. One lifetime was not enough to understand a people and the words they used and the way they thought and lived.

The second sentence is classic free indirect, a clear back-shifting of the contents of Bogle’s consciousness. But that “gold and russet forest” — whose thought is this? Perhaps it really is Bogle’s, as sensitively dictated to Eliza: I was admiring the forest — gold and russet, as I recall … Or perhaps we are reading from Eliza’s novel about Bogle, also called The Fraud, in which case that gold and russet forest may be her detail, a sympathetic embellishment not unlike Mr. Casaubon’s fluttering soul. Then again, perhaps it is the work of Zadie Smith, lightly indulging in a novelist’s word for brown.

Now if I am Smith’s ideal reader, finely aware and richly responsible, then I will find here not a single vibrating consciousness but as many as three, crammed into a handful of words. Which one should I pity? Especially given that they are not on equal footing: Bogle appears to be in Eliza’s hands, and both of them are inexorably in Smith’s.

The irony of Smith’s career is that she has never actually excelled at constructing the kind of sympathetic, all-too-human characters she advocates for. (The closest she came was the affecting portrait of a crumbling marriage in On Beauty.) In truth, Bogle is far less interesting than advertised, the latest in a line of increasingly dull characters dating back to the technically proficient NW. Their studied ordinariness makes us long for Smith’s true strength, which lies not in character but in voice. We read her because she possesses that rare and precious gift of sounding always like herself; because, as an early admirer said of Eliot, “We are in the presence of a soul.” True, anyone who has read the irritating experiment in first-person narration that was Swing Time will agree that the last thing we want Smith to write about is herself. “I have been both adult and child, male and female, black, brown, and white, gay and straight, funny and tragic, liberal and conservative, religious and godless, not to mention alive and dead,” she wrote in the 2019 essay. But what moved us was the reverse: These people had all been her.

So if I really do encounter an ethical other in The Fraud, it is Smith herself: her rippling intellect, her unmistakable sound. Eliza, Bogle, and the rest are other others, strangers who, precisely because Smith has so finely enmeshed her consciousness with theirs, necessarily overflow my ethical capacities. I will simply never get them alone. Smith admits that fiction runs “the continual risk of wrongness” — racial caricature, for instance — and she allows that Eliza may be treating Bogle like a lifeless “scarecrow,” one she is determined to stuff with a soul. For Smith, this is the great ethical drama: How will we mistake each other this time? Perhaps she is even right that the infinite rehearsal of this drama can teach readers a fine feeling for humanity. But the humanist’s mistake is to suppose that politics is just lots and lots of ethics. Ethics asks us to recognize that the other has a soul; politics asks us to reject the soul as a precondition for moral interest. In this sense, fiction has always been an exercise in political consciousness. It asks me to care about people I do not know and will never meet, people who might as well not exist as far as my own life is concerned but whose destinies are nonetheless obscurely intertwined with mine. Not for nothing do we call it the third person.

The author of White Teeth knew this. The Iqbal twins, long separated by gulfs of geography, ideology, and personal feeling, try to bury the hatchet by meeting in a “neutral place.” But soon, they “make a mockery of that idea,” reenacting memories, quoting mentors, relitigating the hoary tale of their mutineer ancestor. A novel is never a neutral place: Every attempted encounter with the other is interrupted by the hysterical crowd, their noses pressed up against the glass. It was true that Smith’s creations in White Teeth were “luminous disks of a pre-arranged size,” as Forster once said of flat characters, their inner and outer lives forming a single glossy Möbius strip. And it was true that Smith sometimes wrote too blithely of people unlike herself. (There was an Arab family that named all their sons Abdul.) But Smith’s characters did not lack humanity so much as she lacked a use for it. Her eye was trained on a collectivity: the vibrant Willesden Green of her youth. In her own way, Smith had written a condition-of-England novel not unlike Middlemarch; with Icarian optimism, she had launched herself directly at the social whole, and in falling, she seemed to fly. Accordingly, Smith never asked too much of her unlikely people. They hit their marks, said their lines, and disappeared, check in hand, back into the crowd. You could tell they had better things to do than be furniture in someone’s novel.

So sympathize away! No one can stop you. But neither the novel nor its people are so weak that they would collapse if our hearts did not bleed for them. Indeed, it is precisely because we feel that characters in novels are real that we can politically object to the way a writer treats them. This may be what the youngs were saying — not that they feared for their own sensitive souls but that they wished to know how to do real justice to imaginary people. How might Smith have answered them? She dislikes the adage “Write what you know” on the grounds that it is now used to keep novelists within the bright chalk circle of personal identity. So for her sake, let us look somewhere more morally serious. The mid-century literary critic F. R. Leavis once wrote, in his very serious book The Great Tradition, that Austen’s genius was to take “certain problems that life compelled on her as personal ones” and impersonalize them, tracing carefully out of herself and back into the world. What Leavis admired was not that Austen had “stayed in her lane”; it was that she’d had the good sense to ask where it led. This is a splendid notion. It suggests that, for any novelist, there exists a small number of historical problems that, for reasons of luck and temperament, she naturally grasps as the stuff of life. The genius lies in knowing which ones they are.